Last January, Stanford University and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France jointly released a vast online collection of documents and images from the French Revolution via the French Revolution Digital Archive. With around 14,000 high-resolution images, it is an overwhelmingly large collection but the website is thankfully very user-friendly with content tagged in multiple ways and organised according to various themes. This is undoubtedly a fantastic resource for not only historians but also a wider audience interested in the tumultuous events of the late eighteenth century considered by many to mark the start of political modernity.

Drawn into the archive, I spent quite some time trawling through it with a particular eye for caricatures, satirical illustrations, and other allegorical depictions of the revolution. Here is a selection of a few of the images I found most striking or noteworthy along with translations and contextual information where necessary. Hopefully these will be of some interest to readers of this blog. I won't say that I am a an expert on this period, but I am fascinated with this period of history and a life long interest in political art. Needless to say, this has been a real educational opportunity for me and has taken up quite a bit of time which I should have been doing something else...

Patriotic Hunt of the Great Beast (1789) [link]

“Posterity will tell us that in 1789 on the 12th July around four o’clock in the evening, several people claimed to have seen in the vicinity of Paris, on the road to Versailles, a Beast of an enormous size and a shape so extraordinary as to have never before seen the like. The news spread universal alarm in the city and put its people in a state of violent agitation. Cries of “to arms, to arms” were heard everywhere without any being found; it seemed that the Beast had swallowed them all along with their munitions. New weapons as extraordinary as the animal that had to be combated were immediately forged. On the 13th, people continued to agitate themselves, arming themselves and running after the Beast without being able to encounter it. On the the following day of the 14th, forever memorable for the France that suffers, a hundred thousand individuals ran to the Hotel des Invalides from which they carried away canons and sixty thousand rifles, such that there were two hundred thousand armed men who tracked down the Beast everywhere. Suspecting that it had retreated to the Bastille, the people flew to it with heroic courage and this lair of Despotism, despite its hundred bronze mouths vomiting fire, was taken by assault in two hours. With this victory appeared the monster with a hundred heads; its hideous form revealed that it was of an aristocratic kind; suddenly our bravest hunters seized upon her from all sides and it was to whom would cut the most heads. This monster that dragged behind it desolation, famine and death disappeared instantly under a hundred different forms and fled languidly abroad, taking with it the despair and shame of its defeat.”

The Revolution of 1789 or the Conquest of Liberty – Heroic Allegory Dedicated to the Nation (1789) [link]

We have here a rich phantasmagorical image in which we see the revolutionaries crowd around a statue of Liberty with her Phrygian cap set on a rather weary “ship of state” surrounded by rowing boats named after different regions of France. Above each of the canons pointing out of the ship’s port holes are inscribed the principles of the new order: “declaration of rights”, “feudalism destroyed”, “privileges abolished”, “armed citizens”, “popular elections”, etc.

The early revolution took aim at aristocratic power and perceived abuses of power such as the lettres de cachet but not at the monarchy itself. So atop the ship’s highest mast flies a flag that proclaims “the Law and the King” and the monarch is here favorably depicted in the foreground. He is “happy with the success” of his people, the text below tells us, his “throne shining with more majesty” as it becomes “the altar of laws and liberty.” You have to look to the right of the image to see figures of oppression being ousted, carrying with them chains and the aforementioned lettres de cachet - their seemingly oriental appearance presumably a play on Enlightenment associations of the Orient with despotism. In the top left is a castle with its defeated residents – it doesn’t particularly resemble the Bastille so my guess is this is a stand-in for foreign powers (the coat of arms would probably identify them more accurately).

Regeneration of the French nation (1789) [link]

Another image from the early days of the Revolution, it depicts France in the figure of a woman whose chains have been cast off by cherubs and is illuminated by heavenly figures holding the scales of justice and beaming the light of Reason at her. At her side is Louis XVI wielding a sword in his right hand and holding in his left a piece of paper on which the word “constitution” is inscribed. France is casting bolts of lightening at a monstrous assortment of noblemen, tyrants, and priests, toppling the Bastille and setting fire to papers on which we find “superstition”, “slavery”, “privilege”, and “the orders.” To the left of the image are the enslaved four corners of the world, joyously witnessing the spirit of liberty manifest in the “triumph of France.”

Mortals are equal – it is not birth but only virtue that makes the difference (1794) [link]

At the centre of is image is Reason (above her head is “the sacred flame of the love of country”) who puts on a same level the “white man” and “colored man.” The latter holds in his hand the declaration of the rights of man as well as the decree of the 15th May 1791 that recognised the equality of rights to non-whites in the French colonies… as long as they were born of free parents.

The French Genius/Spirit adopts Liberty and Equality (1794) [link]

Liberty armed with the scepter of Reason blasts Ignorance and Fanaticism (1793-95) [link]

I shit on the aristocrats (1790) [link]

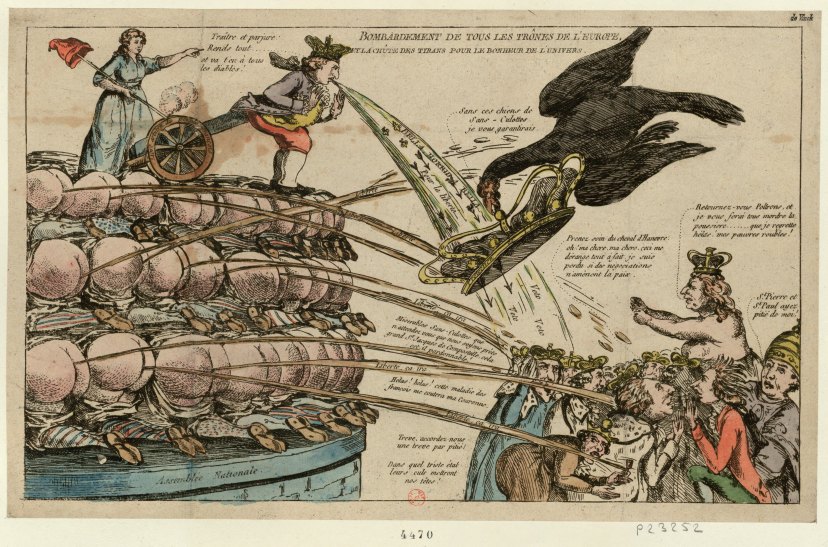

Bombardment of all the thrones of Europe (1792) [link]

In this rather arresting output of the scatological imagination, the National Assembly sprays the crowned heads of Europe and Papacy with the scented juices of liberty. A “violent emetic” is fired into the French King’s rear from a cannon on which can be read “the free will of the French people”, the monarch spewing the Latin words bella horrida bella (“wars, horrible wars”). The Sans-Culotte behind him harangues him: “Traitor and perjurer. Give [vomit] it all back… and go to hell.” The mood is increasingly turning against the king.

Dialogue: I lose a head / I find one (1793) [link]

Ceci n’est pas une guillotine.

This is the Guillotine (1793) [link] and this is not a Rene Magritte painting....

The People devourer of Kings. Proposal for a colossal statue to be placed at the most eminent points of our borders (1793) [link]

Robespierre guillotining the executioner after have guillotined all the French (1794) [link]

The Terror is in full swing. Robespierre is sitting on an obelisk on which is inscribed “Here Lies all of France” and is trampling the constitutions of 1791 and 1793. Behind him is a sea of guillotines, each associated with particular groups that fell prey to revolutionary justice, among which noblemen and priests, military men, Girondins, Jacobins, the National Convention, the Committee of Public Safety, “people of talent” and “old people, women and children.” Robespierre would of course himself meet the same end in July 1794.

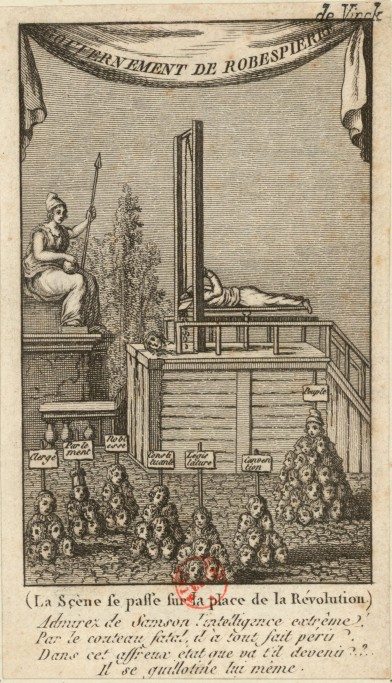

The Governement of Robespierre (1794) [link]

“Admire the supreme intelligence of Sanson. By the fatal blade, he has made everyone perish. What will he become in this dreadful state? He guillotines himself.”

Issued from an illustrious family of executioners, Charles-Henri Sanson was responsible for releasing the guillotine on Louis XVI, Robespierre and Danton among the almost 3,000 individuals he executed during his long career.

A little dinner, Parisian-style – or – a family of Sans-Culottes refreshing, after the fatigues of the day (1792) [link]

An image from England, by James Gilray where revolutionary violence and regicide were received with widespread horror. Caricatures of the time commonly depict the Sans-Culottes as a monstrous affront to civilised values with the English constitutional monarchy favourably compared to the perceived ungodliness of the revolution.

Hell Broke Loose, or, The Murder of Louis (1793) [link] They were definitely freaking in England!

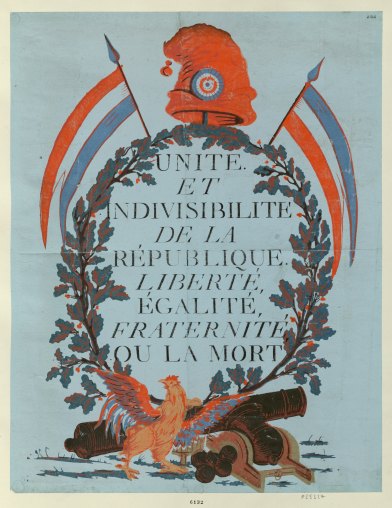

Unity and Indivisibility of the Republic. Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, or Death (1793) [link]

As the revolution radicalises and the French republic is drawn into protracted wars with the remaining monarchies of Europe the rallying cry of the nation becomes the uncompromising “liberty or death.”

Bonaparte, First Consul of the French Republic (1802) [link]

The years of war that ensued would eventually see the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte with the 18 Brumaire coup in 1799, heralding the end of the revolution and the Republic formally giving way to the Empire in 1804. This engraving commemorates the Battle of Marengo of 1800 in which Bonaparte led the French army to victory against the Austrians, thereby strengthening his grip on power following the coup.

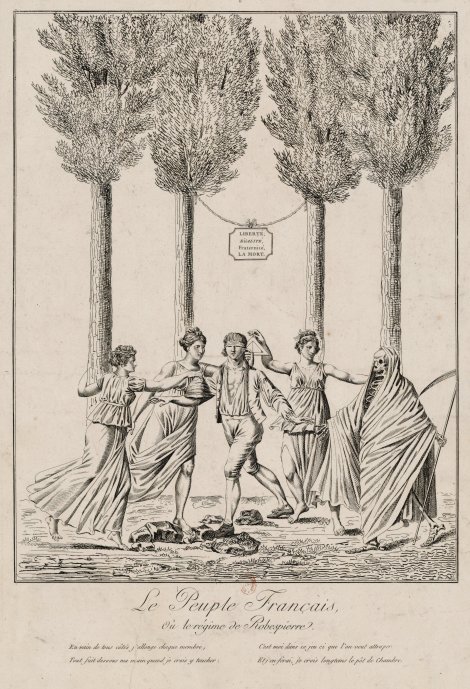

The French people or the regime of Robespierre (1794) [link]

The sign hanging from the liberty tree reads “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, Death” with each idea embodied by one the characters surrounding the blindfolded Frenchman. The text below the image says:“In vain I extend my members on every side;All flees from beneath my hand when I think I will touch it;In this game it is I that one wants to catch;And I will long be, I believe, its chamber pot.”

2 comments:

This is great: thanks for the info.

the Ol'Buzzard

Good read

Post a Comment